From a Philadelphian founding father to modern day energy drinks, the history of content marketing is long and twisted. Born out of advertising and marketing, content marketing started growing its own branch on the Marketing Tree about 300 years ago, when Benjamin Franklin was marketing his printing business.

To track content marketing’s early history, we’ll have to go back to when there was just one medium: paper.

Content marketing: an approach as old as America

Ben Franklin was more than a founding father, diplomat, scientist, inventor, author, printer, political philosopher and theorist, musician, postmaster, civil servant, meteorologist and kite enthusiast – he was also one of the very first content marketers. When he published the first edition of Poor Richard’s Almanack in 1732, Franklin leveraged content that people actually wanted to read to market his printing business.

The content resonated with an increasing number of readers, and Franklin found a way to influence people and public opinion while also enjoying the benefits of his roaring printing business. He continued to publish the Almanack annually for 25 years. Franklin’s collection of poems, reviews, observations, weather, prose and sayings was extremely popular, selling 10,000 copies a year, according to History.com. Franklin’s content helped cement him as one of the all-time thought leaders in history, and proved an early lesson in content marketing: If you give your audience a reason to engage, your brand will be top-of-mind.

The making of a modern market

Fast forward a century and a half to 1900. Printing presses have become more efficient, distribution of content is wider reaching and the population has grown larger and more literate. There’s an increasing opportunity for delivering content to a receptive audience.

Michelin: Driving brand awareness through content

The Michelin Guide was first published in 1900 when there were just 3,000 cars in France. Andre and Edouard Michelin proved that brands could increase sales and awareness by creating great content. They began publishing guides to local attractions to give more people a reason to purchase cars – more car sales meant more Michelin tire sales.

Michelin also was able to use the guide to position itself as more than a tire brand. The restaurant- and hotel-oriented guide books established the brand as a cultural presence around major world cities. Today, when you Google “Best food in Manhattan,” Michelin is still likely to show up in your results, and you’ll be just one more click away from viewing tires and comparing prices.

Jell-O: Educational content shows the audience a brand’s value

Four years after Michelin published their first guide book, another household name was jiggling its way onto the content marketing scene. Jell-O was dealing with stagnant sales of their powdered mix as well as low brand awareness, as Lumos Marketing reported. The company began sending representatives door-to-door to spread the word about all the recipes you could make with a box of their mix. The recipe pamphlets were free, helpful and easily actionable.

Unlike Michelin and Franklin’s nuanced content marketing strategies, which involved discussing indirectly related topics, Jell-O’s approach was less subtle. Their product was much more straightforward, so their content could afford to be more direct, product-oriented and digestible. The content approach worked, and according to Lumos’s report, Jell-O’s sales quickly bumped up by over $1 million.

Mid-century marketing meets the middle class

The middle of the 20th century saw the mainstream development of native advertising in the form of unique content offerings: soap operas and cereal boxes. The American middle class was emerging as a strong target for content marketing, and one of the best ways for brands to reach them was in living rooms and kitchens.

Soap operas: Bringing native ads into homes with content

Underneath the sudsy layers of poorly acted, sentimental melodrama, soap operas started out as subtle content marketing – and more specifically, native advertising. Procter & Gamble began broadcasting branded radio content in the early 20th century. They designed many of their products for women, and suitably designed their programming to appeal to women as well. These radio dramas eventually moved to television, where we now know of them as soap operas.

Once Procter and Gamble laid the groundwork of building a fanbase of adult women, they were then able to seamlessly intersperse their marketing messages into the entertaining content. The soaps taught an early lesson about native ads: if marketing fits the form and function of the content and platform it’s delivered on, audiences will be engaged.

Cereal boxes: Targeted content keeps your customers buying

Ever been captivated by the back of your cereal box so long that your breakfast turned to mush? A New York Times feature on the history of cereal marks the 1950s as the decade when brands began targeting cereal to kids. During the baby boom, Kellogg’s began focusing on selling sugary cereal specifically to kids. With this shift in business model came friendly animal mascots, colorful animated commercials and the back of the cereal box as a form of targeted content marketing.

A box of cereal is designed to capture kids’ attention, and brands go about it in a wide variety of ways: Some use pictures, infographics and stories, while others offer prizes from partnered brands, or push their online content. The more fun or informative the content on a cereal box is, the more memorable the brand is to its audience, and their parents.

When cereal boxes and the three TV networks were some of the only platforms for marketing, the playing field for content was fairly level. The internet’s reach very quickly made content marketing more competitive.

The beginning of the Internet Age

Increasing access to high-speed internet helped content marketing become a mainstream form of marketing. Just as Franklin’s content marketing efforts relied on widespread literacy and printing technology, 21st century content marketing relies on widespread connectivity.

By the late 2000s, when YouTube, Facebook and Twitter had established themselves as social fixtures on the web, content was an important intellectual currency. Online content marketing was, and remains, on-demand, digital, shareable, repurposable and accessible worldwide.

Oreo: Timeliness and tech for the win

As the social web became a more powerful avenue for content marketing, brands began getting creative with social marketing. Charities, for one, found success with “Tweetathons,” some organizations made use of social media contests and conversations, and other comapnies created branded entertainment designed to be shared.

Oreo creatively leveraged their shareable content at Super Bowl XLVII. When the power cut out at halftime, the brand was quick to tweet about it. Not only was Oreo’s response almost instant, but it naturally incorporated a trending topic into the cookie company’s social strategy.

Power out? No problem. pic.twitter.com/dnQ7pOgC

— Oreo Cookie (@Oreo) February 4, 2013

Marketing innovations like this helped to usher in the modern content era. Content marketing still exists in the physical world – Trader Joe’s relies on entertaining paper mailers and your favorite neighborhood bar likely still catches foot traffic from punny sidewalk signs – but for the most part, content has moved online.

Brafton and today’s integrated content scene

Modern content marketing is so integrated into our online content experience that setting your own brand’s marketing efforts apart from the rest has never been more challenging.

“The marketplace in 2008 was undeveloped,” CEO Richard Pattinson said of content marketing when Brafton first opened its doors. “Most brands had websites, but many were little more than digital brochures, and they were often outranked by black hat practitioners. Our response to the climate in 2008 started as a news-based, value-driven service, and over the next few years, we grew it to cover everything.”

Today, brands are blending content marketing into their day-to-day online marketing output. Marketers won’t be able to literally re-invent the wheel like Michelin did 116 years ago, but now the way to gain traction is to provide relevant content to your target audience.

“Ideation and research are robust processes, and working to match user intent is paramount to creating content that resonates,” Pattinson explained.

Your content has to be great. In fact, it has to be so great that it will compete with, and beat, every other piece on the same topic.

An effective modern-day content initiative can even build a brand’s presence without ever mentioning its product. Many brands are even producing high-budget videos and other marketing collateral without forcing a sale or making their audience think of the product if they aren’t in buy-mode.

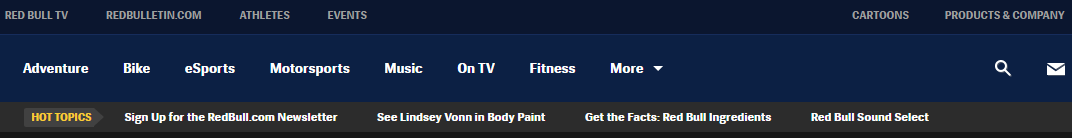

Take a look at RedBull’s website navigation:

The core products are energy drinks, but as you can see there’s almost no mention of the beverages on their website at all, even on their online store. RedBull’s drinks have been on the market for decades. Now the company’s mission is to communicate why they should be part of your lifestyle. Using videos of stratosphere skydiving and flying machine competitions, RedBull is becoming more of a digital producer than a soda company. The one common thread in all of their content: It gives you a rush and suggests their product does too.

It’s only taken 300 years for content marketing to evolve from a mechanical printing press to targeted content that travels digitally across the globe at the speed of light. Content marketing is growing subtler and more dynamic. We’re so increasingly connected with people and brands across countless formats and platforms, that we don’t even notice content marketing when we’re interacting with it. By the 2020s, we’ll likely refer to “content marketing” simply as “marketing.”